When it’s hard to cope,

When it’s hard to cope,

don’t leave me.

When there’s not much hope,

don’t leave me.

When I don’t understand,

don’t leave me.

When I won’t hold your hand,

don’t leave me.

When you see a better man,

don’t leave me.

When you realise that you can,

don’t leave me.

When you balk at all your duties,

don’t leave me.

When you see me flirt with beauties,

don’t leave me.

When we fight and the police intervene,

don’t leave me.

When your blood leaves a mess at the scene,

don’t leave me.

When I pace the whole day at your bedside,

don’t leave me.

When I show you the peace of the dead side,

don’t leave me.

I need you,

don’t leave me.

When it’s hard to cope,

don’t leave me.

When there’s not much hope,

don’t leave me.

When you don’t understand,

don’t leave me.

When you won’t hold my hand,

don’t leave me.

When I see a better man,

don’t leave me.

When I realise that I can,

don’t leave me.

When I balk at all my duties,

don’t leave me.

When I see you flirt with beauties,

don’t leave me.

When we fight and the police intervene,

don’t leave me.

When my blood leaves a mess at the scene,

don’t leave me.

When you pace the whole day at my bedside,

don’t leave me.

When you show me the peace of the dead side,

don’t leave me.

I need you,

don’t leave me.

This one is really going to mess up the word cloud.

I was listening to a podcast while waiting for the bus, where a woman says ‘ne me quitte pas‘ (don’t leave me) to her husband who is in a coma. This reminded me of a more well-known use of this phrase, in the song of that name by Jacques Brel, in which he is presumably saying it to a lover who is not in a coma. So I thought perhaps I could write a poem that starts off with that kind of sweet sentiment, but gets more and more extreme until it’s clear that it’s about an incredibly controlling, violent man who simply will not allow the woman to leave him, a black turn which would be either funny or awful, depending on your sense of humour.

Then I went and ruined any possible humour by considering the same poem from the perspective of the kind of helpless, dependent woman who is so entrenched in the bad relationship that she does not care what the man does to her, as long as he does not leave her. And it’s just not funny. Don’t worry, next week I will write a nice uplifting poem about death. Or something thoroughly horrible.

After I’d written the first six lines (not counting the ‘don’t leave me’ ones) I noticed that I had two in third-person, two in first-person, and two in second-person. What’s more, each rhyming pair had one more syllable than the previous. So I decided to continue that way. I didn’t keep the same order of third-first-second person in the second half, but I did make sure that I used a pair of each. I switched between iambic and anapaestic lines as necessary (always with the anapaest at the beginning) to make the line lengths seem natural. It certainly made it interesting to write. The only real casualty was the line about blood, which I would have left as ‘When you/I leave too much blood at the scene’ if it didn’t have to be in third-person. Also, ‘when I realise that I can’ messes up the rhythm somewhat, if you put the emphasis on the ‘I’ to make it make sense. I considered leaving one or both of those as ‘you’, but I decided that if I was going to change something from the pattern, it had better be something worthy of the extra attention that would get it, and I didn’t think it was.

If you prefer to think of the ‘bad guy’ as a female, you have the choice of either replacing ‘man’ and its rhyme, or switching the pronouns on those lines and rewriting two other lines to compensate. I’ll leave that as an exercise for the reader.

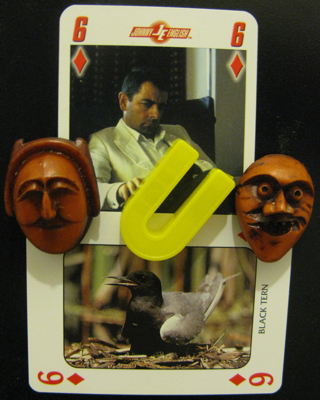

The connection with the letter ‘U’ only really exists in the picture. There are two faces, one angelic and one mad (either insane or angry or Van Gogh, I can’t work it out. I couldn’t find the really evil-looking face) This either represents the man’s two faces, or the two people in the relationship. Either way, the U is the crooked union of the two, since it resembles the union symbol in mathematics. Either that, or it is pronounced ‘you’, and the sour-looking man has you in his grip.

I think this forced march approach to writing is working. Last week I wrote one and a half poems with seven hours to spare. This week, instead of continuing with the half-poem, I came up with a new idea on Monday morning before even looking at the cards. This idea turned out to match a few of the cards, so I went with it. Then, on Thursday, I came up with the idea for the thoroughly horrible Thing mentioned above, which I will write in a later week. So I have two spare ideas at this point, and I finished this week’s poem on Saturday. I hope I don’t run out of weeks before I run out of ideas. Or maybe I hope I do.

#1 by mtgordon on February 3, 2009 - 12:21 am

I’ve also had good luck with forced march poetry. I have especially good luck writing while traveling; the down time waiting in airports or sitting strapped in a seat can be highly productive. It beats doing the sudoku in the in-flight magazine.

LikeLike

#2 by Angela Brett on February 3, 2009 - 12:47 am

Travelling is great. I’ve found that trains are the best environment for writing poetry. No internet, no other distractions, no noise, just time, scenery, paper and pen. A few of my favourite Things have been written on trains.

Hmm… I should write a song about my favourite Things. But to what tune? 😉

LikeLike

#3 by rice1077 on February 11, 2009 - 10:35 pm

What a great poem… I really enjoyed the way it flowed.

LikeLike