I started writing this post in 2020 (it was last edited in August that year) but at some point decided everybody knew this stuff and there was no point posting it. Well, Stewart Lynch’s talk at Deep Dish Swift reminded me that there’s always somebody who doesn’t know something. Besides that, I originally got the idea for this by noticing things that my co-workers were not doing. I am attending James Dempsey’s App Performance and Instruments Virtuoso course at the moment, so I want to get these tips out there before I learn 100x more about the available tools.

There’s more to tracking down bugs than pausing at breakpoints or adding log statements. Here are some techniques which you might not use or might not think of as part of debugging. These are all explained from an Xcode perspective, but similar methods should exist in other development environments.

Quick-Reference Chart

This chart should help you figure out which techniques to use in which situations — ask yourself the Entomological Taxonomy questions along the top, and check which of the Extermination Techniques have a ✔️in all the relevant columns. To make the table more compact, I have not included rows for responses where all the techniques are available — for most of the questions, if you answer ‘yes’, then you can ignore that column because answering yes does not limit which techniques you can use.

More details on both the Entomological Taxonomy and the Extermination Techniques are below.

- Quick-Reference Chart

- Entomological Taxonomy

- Does the bug stay the same when paused or slowed down?

- Did it work previously?

- Do you know which code is involved?

- Is it convenient to stop execution and recompile the code?

- Can you reproduce the bug reliably?

- Is there a similar situation where the bug doesn’t appear?

- Are you ignoring any, errors, warnings, exceptions, or callbacks?

- Is the bug related to macOS/iOS UI?

- Extermination Techniques

- Any more ideas?

Entomological Taxonomy

Not all debugging techniques are appropriate in all situations, so first it helps to ask yourself a few questions about the bug.

Does the bug stay the same when paused or slowed down?

Some errors go away when you slow down or stop execution. Sometimes timeouts give you a different error if you pause execution or even slow it down by running in a debugger with many breakpoints turned on.

Did it work previously?

If the code used to work but now doesn’t, the history in source control can help you work out why.

Do you know which code is involved?

Early in the debugging process, you may have no idea which part of the code causes the error, so some techniques are less useful.

Is it convenient to stop execution and recompile the code?

If it takes a complicated series of steps to reproduce a bug, or if it only happens occasionally and you’ve just finally managed to reproduce it, or if your code just takes a long time to compile, you’ll want to debug it without stopping to make code changes.

Can you reproduce the bug reliably?

This one is pretty self-explanatory — if you know how to make the bug appear, you have an advantage when trying to make it disappear.

Is there a similar situation where the bug doesn’t appear?

If you can not only reproduce the bug but also know of a similar situation when the bug doesn’t occur, debugging is more of a game of spot the difference. This is where diffing tools could help.

Are you ignoring any, errors, warnings, exceptions, or callbacks?

Have you heard the expression ‘snug as a bug in a rug‘? Sometimes the cause of the bug is right there under the rug where someone swept it.

Is the bug related to macOS/iOS UI?

UI issues are harder to unit test, but there are a few techniques specific to macOS/iOS user interface.

Extermination Techniques

Here are some debugging methods I know about. Most of these methods are available in many different environments, but I’ll be describing specifically how to use them in Xcode. Feel free to comment with other methods, and perhaps I’ll include them in an update post later.

The Debugger

Ah yes, the most obvious tool for debugging. The debugger is particularly useful when it’s not convenient to stop execution and recompile. You can also share your breakpoints with other developers through source control — a fact which I did not know until I started writing this post. I initially had the question ‘Do other developers need to debug the same thing?’ in the Taxonomy section, but I think all these techniques work either way.

Interactive breakpoints

This is what you probably first think of when you think of breakpoints. It’s what you get when you click in the gutter of your source file. When the breakpoint is hit, execution stops and you can examine variables (in the UI or with the p or po commands), the stack, etc, and run code using the expr command. See Apple’s documentation for more information on adding breakpoints and what you can do with them.

Automatically-continuing breakpoints

If the behaviour changes when you pause in the debugger, you can still use breakpoints to log information or run other commands without pausing. Secondary-click on a breakpoint to bring up a menu, then choose Edit Breakpoint to show the edit pane. Set up a Log Message or other action using the ‘Actions‘ menu, and select the ‘Automatically continue after evaluating actions‘ checkbox to prevent the debugger from pausing at this breakpoint.

You can use the search box at the bottom of the Breakpoint Navigator to find which breakpoints any logged text might have come from.

Unless the debugger itself slows down execution enough to change your app’s behaviour, this is better than using log statements. You don’t need to stop execution to add logging breakpoints, and you are less likely to accidentally commit your debugging code to source control.

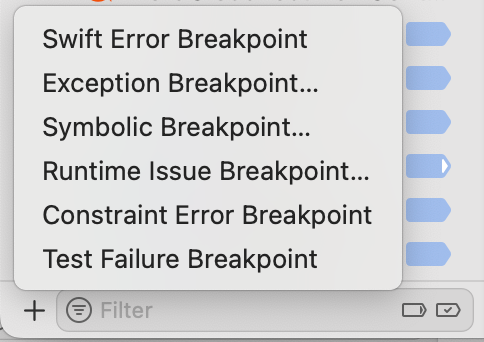

Symbolic breakpoints etc.

The kinds of breakpoints above are great if you know which code is affected. If you don’t know that, you’ll find some other kinds of breakpoints in the menu that pops up from the + button at the bottom of the Breakpoint Navigator.

These will stop at whatever part of your code certain kinds of issues happen.

Constraint Error Breakpoint in this menu can be useful for debugging UI issues when you’re using AppKit or UIKit.

Debug View Hierarchy

If your UI layout is not how you expect it to be, you can use the Debug View Hierarchy button![]() on the debug bar to see exactly where and what size each view is. You can drag the representation of the view hierarchy around and look at it from the side to see how views relate to the views behind them.

on the debug bar to see exactly where and what size each view is. You can drag the representation of the view hierarchy around and look at it from the side to see how views relate to the views behind them.

Code Changes

If it’s convenient to stop execution and recompile the code, you can make some code changes to help you track down bugs.

Unit test to reproduce bug

If you can write a unit test that reproduces the bug, you can run that in the debugger to find out what’s going on, without the hassle of going through multiple steps in the UI to set up the buggy situation. It will be much quicker to find out whether your fixes work, and to make sure the bug stays fixed later.

UI test to reproduce bug

Same as above, but this can be more useful than a unit test if the bug is related to UI layout. It also works even when you don’t know which code is causing the issue.

Ad-hoc log statements in code

Ah, our old friend print/NSLog… a common quick go-to when debugging. In general I would recommend using breakpoints instead (either interactive, or logging the data you would have printed and continuing) because you can add them without recompiling, and you don’t have to remember to remove the logging later. But in some situations, even running in the debugger can slow down the code enough to change the behaviour, so you might need to use logging.

You can also use logging APIs or other telemetry solutions for recording what happens in your app in a more structured and permanent way, but that is outside the scope of this post.

Adding all optional error handling

If you’re calling any functions which can throw exceptions, or return errors (either using an optional error parameter, or a return value) or nil where that would be an error, make sure you’re checking for that. If you have control over those functions, change them so that it’s impossible to ignore the errors. I once fixed an error which had been plaguing my co-workers for years, just by passing an optional error parameter into a system function and checking the result.

Fixing compiler warnings

If you have any compiler warnings, fix them. If you’re debugging a specific issue, first fix the warnings in the relevant code and see if it helps.

Later, whenever you have more time to work on technical debt, fix all the rest of them. Then set ‘Treat Warnings as Errors‘ to YES in the Build Settings of your target. Then search for ‘warnings’ in those build settings, scroll down to the Apple Clang – Warnings sections, and gradually turn on more of the optional warnings. You can use a tool such as SwiftLint to warn about even more things, such as force unwrapping, and then fix all of those warnings. If you’re using Swift 5, enable Complete concurrency checking, fix all of the warnings that gives you (if you’re new to Swift Concurrency and don’t fully understand what the warnings mean, I found these videos from WWDC 2021 and WWDC 2022 gave a useful overview) then upgrade to Swift 6.

Your compiler can find potential bugs before they happen, so you never even have to debug them. Put it to work!

Git

If the code used to work, chances are you can use git (or whatever source control system you’re using) to figure out when it last worked and what change broke it.

If you find the commit that caused the issue, and the commit message mentions a ticket number, check the requirements in the ticket and take them into consideration when fixing the bug. Sometimes I have found out that a reported bug it really isn’t a bug, it’s a feature that was forgotten about! Other times, it’s a real bug but it has to be fixed very carefully to avoid breaking a feature or bringing back a different bug.

Git Authors

If you know pretty much where in the code the bug probably is, then even if you don’t know when it broke, you can see the latest changes in those lines of code. Switch to the source file in question, and show the Authors view using Authors in the Editor menu. You will see a new sidebar with names, dates, and (if there’s room) commit messages relating to the latest change in each line in the source file.

If you click on one of these commits, you can see more information about the commit:

Tap on Show Commit to see what changed in that commit. Maybe you’ll see how it caused the issue.

Note, this feature is also known as git blame, but Xcode calls it Authors, because we shouldn’t feel bad about having written code, even if we did cause a bug.

Git file history

If you know which file the issue is probably in, but not necessarily which part of the file, you can see the history of the file by opening the History Inspector with View → Inspectors → History.

You can click on each change and get a popup similar to the one above, where you can click Show Commit to see what changed.

Git project history

If you have no idea which code could cause the issue, but you have a good idea of when the issue was introduced (this is starting to sound like quantum physics) you can look at what changed in the whole project during the likely time interval. I usually do this directly on the GitHub website for projects that are using GitHub, but it looks like you can also see the list of changes by selecting a branch in the Repositories section of the Source Control navigator in Xcode.

Git Bisect

I’ll be honest; I’ve never actually used git bisect, even though I remember hearing about bisection before git even existed. But it seems like a very efficient way to find which changes caused a bug! It essentially lets you do a binary search of your commit history to find the problematic commit. Combined with a unit test to reproduce the bug, this could be very quick.

Diff

The above section covers looking at what changed if some code used to work, but doesn’t any more. But if instead the code works in some situations but not others, you can still compare things using a diffing tool. I tend to use FileMerge, because it’s installed by default. I usually search for it in Spotlight and open it directly from /Applications/Xcode.app/Contents/Applications/FileMerge.app, but I just noticed you can open it from the menu in Xcode using Xcode → Open Developer Tool → FileMerge.

Code diffing

If the code for a situation that has a bug looks similar to the code for the situation which doesn’t have a bug, copy the relevant code into two text files (or paste it straight into your favourite diffing tool) and see what’s different.

Tip: Once you are sure of exactly what’s different between the two pieces of code, you might also want to refactor to reduce the code duplication. Even if you’re not debugging, if you ever find what looks like duplicated code, always run it through a differ to make sure it’s really identical before extracting it to a function or method.

Log diffing

If the buggy situation uses mostly the same code as the non-buggy situation, but some data or behaviour causes it to behave differently, you can add logging (either logging breakpoints, or print statements, as discussed above) to show what is happening at each step. Then use your favourite diff tool to compare the logs for the buggy situation with the logs for the working one.

Any more ideas?

These are some of the debugging techniques I use all the time. But just as I’m betting that someone out there doesn’t know them all, I bet there are more debugging techniques I don’t know about which seem basic to other people. What are yours?