Posts Tagged prose

Queen of Clubs: A History of the Large Hadron Collider, part I: Conception

Posted by Angela Brett in CERN, Writing Cards and Letters on September 15, 2008

Between March 21 and 27, 1984, theorists, experimentalists, accelerator physicists, and experts in superconducting magnets gathered for a workshop in Lausanne and Geneva. They were not there to discuss the Large Electron Positron collider, for which excavation of a 27km near-circular tunnel would soon begin at CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research. They had come to discuss a possible playmate for the LEP, a collider of protons and perhaps antiprotons to be installed alongside the LEP in the same tunnel. Some nicknamed it the Juratron, after the Jura mountains under which part of it would pass. Officially, it was known as the Large Hadron Collider, or LHC.

Between March 21 and 27, 1984, theorists, experimentalists, accelerator physicists, and experts in superconducting magnets gathered for a workshop in Lausanne and Geneva. They were not there to discuss the Large Electron Positron collider, for which excavation of a 27km near-circular tunnel would soon begin at CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research. They had come to discuss a possible playmate for the LEP, a collider of protons and perhaps antiprotons to be installed alongside the LEP in the same tunnel. Some nicknamed it the Juratron, after the Jura mountains under which part of it would pass. Officially, it was known as the Large Hadron Collider, or LHC.

The LHC would accelerate protons to an energy of up to 9 TeV, more than nine million times the energy of a proton at rest. To keep such high energy particles on course in a ring as small as the LEP, the LHC would need superconducting magnets with a magnetic field of 10 Tesla, about 2000 times the strength of a refrigerator magnet (pictured.) The superconductor technology available at the time could theoretically be extended to create magnetic fields of up to 6 or 7 Tesla, but substantial new developments would be necessary to reach the required 10 Tesla.

Carlo Rubbia concluded the workshop with the statement, “Perhaps the time has come for us to pause, at least until the magnet, accelerator, and detector issues have made some significant progress.” There would be no playmate for LEP just yet, but it would come.

The LEP tunnel was made big enough to fit two accelerators. By the end of 1986, only half a kilometre of it remained to be dug. A preliminary technical study on the possibility of building the LHC on top of the LEP was carried out, and it seemed like a better deal than the alternative proposition of a 1 TeV linear electron-positron collider. With the LHC and LEP together, electron-positron collisions, electron-proton and proton-proton collisions would all be possible, with protons injected by CERN’s existing proton accelerators. Nobody had managed to make strong enough superconducting magnets yet, but there was optimism that it was possible.

In 1987, the first LEP magnet was installed in the newly-completed tunnel, and the first model of an LHC dipole magnet was made. To save space and money, the two opposing proton beams would pass through separate channels within the same magnet. Studies were underway of the possibilty of using either niobium-titanium or niobium-tin for the magnets, or perhaps the recently developed ‘high temperature’ superconductors. The next year, a niobium-titanium superconducting magnet was made which could provide a magnetic field of more than 9 Tesla. It was hoped that the LHC would be able to reach an energy comparable to the 20 TeV of the Superconducting Super Collider being built in Texas.

In the early afternoon of Bastille day 1989, physicists were jublilant to see the evidence of the first beam of positrons sent around the LEP: an unassuming white oval on a blue screen. But for all the eyes fixed on the LEP, more than ever were looking forward to its companion, the LHC.

Many studies were carried out on the feasibility of the superconducting magnets, cryogenics, and civil engineering that would be required. All confirmed that such a machine could indeed be constructed. Two models of LHC dipole magnets in niobium titanium, and one in niobium-tin, both produced fields of around 9.4 Tesla. A cost estimation and construction schedule for the LHC were established: it could be put into service by 1998, while only slightly disturbing the functioning of the LEP.

In 1990, more detailed plans of the LHC were prepared, and delegates from CERN member states proposed the idea to their respective states, expecting a decision by 1992. A timely decision would mean that the LHC could start operations in 1998, as predicted, for a cost comparable to that of the LEP. With 9 metre magnets creating a field of 10 Tesla, it would collide two beams of protons with an energy of up to 7.7 TeV each. Four prototype 1 metre long 10 Tesla dipole magnets were ordered from four different companies. A life-sized prototype was constructed, with a field strength of 7.5 Tesla.

On 20 December, 1991, the CERN council unanimously approved the LHC project. By that time, thousands of hours of on supercomputers had been spent simulating the interactions that would occur in the LHC. The council asked that all technical and financial details be worked out by 1993.

Preparations picked up momentum in 1992. A conference in March on the LHC attracted 600 scientists. In October, the LHC Experiments Committee received letters of intent for three possible LHC experiments: ATLAS (A Toroidal LHC Apparatus), CMS (Compact Muon Solenoid) and L3P (Lepton and Photon Precision Physics.)

Although the required 10 Tesla field had already been achieved, it was considered too difficult to maintain. Therefore the decision was taken to elongate the dipole magnets to 13.5 metres by deplacing other elements. This would increase the time that the protons were exposed to the field, lowering the necessary field strength to 9.5 Tesla.

In 1993, two of the proposed experiments, CMS and ATLAS were approved, along with a new proposition, ALICE (A Large Ion Collider Experiment.) In December 1993, exactly two years after the council’s approval of the LHC, the requested information was presented. Construction could soon begin.

Jack of Hearts: Jack

Posted by Angela Brett in Intriguing Development, Writing Cards and Letters on August 17, 2008

The following is a sequel to Ten of Hearts: Double You.

A fair-haired man enters and plays a flashlight over the room. He stops dead as the light finds the face of the oldest of us.

I fight to open my eyes against the burning light. Before it blinded me, I saw something tantalisingly familiar in the man’s gait. When my eyes finally consent to staying open, they see only a bright light against darkness.

The light falls with the sound of a collapsing body, and spreads a gloomy half-light across the floor. I rush toward the unconscious intruder. It’s Jack, or almost Jack… he seems older. I stroke his forehead until his eyes also manage to open again. He looks at me as though he is lost in a familiar place.

After a minute, he pulls away abruptly. “Cat, I killed someone. Did you see?”

“What?”

The others’ reactions remind me that we are not alone in the room.

“Get away from him!” I squeal. I’m eight. I don’t want the big me to be killed. I run toward her and try to drag her away, but she doesn’t move. A six-year-old me comes to help.

“What?” This time it is the man who is surprised. I look at him defiantly.

“He tried to kill me first! I’m a good guy… I think,” he protests.

I look at the big me. “It’s okay,” she says. “I know him. He won’t hurt us. His name’s Jack.”

I relax my grip, but stay at her side.

We listen to the rest of his story.

“About a year and a half ago, I woke up to an old man trying to inject me with something. We struggled, and eventually I injected him with it. He went to sleep immediately. I watched him sleeping. He looked like my grandfather. God, it was awful, thinking I’d killed my grandfather.” His voice is beginning to quaver. “So I tried to wake him, I tried so hard…” his words clump into sobs.

We watch, trying to make sense of the new layer of strangeness. Trying to remember our lives, trying to get back to them.

“But now… I went to heaven anyway…” Jack manages to squeeze past the lump in his throat.

The youngest of us starts crying with him.

“Heaven?” I’m the oldest. The oldest in a group of time-travelling versions of myself. What does that mean? “I was there too, wasn’t I?”

“Yes… yes, of course you were there… you know, don’t you?”

I see my worst fears in his eyes.

“While I was fighting the man, he said… he said, ‘you don’t know how much you want this.'” He paused to find enough calm air to speak again. “After it was over, I realised he was right. You were already dead. I’m so sorry…” Jack buries his face in my lap and weeps.

For a while we just sit there, watching him cry. He is a stranger to most of us, but we can’t help feeling his grief, and mixing it with own for our lost lives.

“Hey, were you in virtual reality too?” I ask. I’m ten, and I’ve been thinking hard to take my mind of my sore knee. It hasn’t really worked, but I have some ideas.

This gets through his despair. “Smart kid… you know all about VR? I used to make virtual reality stuff. I made a lot of money from it. So yes, I’ve been in it.”

“No, I mean… cool, you know all about it? This thing I’m wearing, it’s a virtual reality suit, right?”

Jack looks at me for the first time. He picks up the torch and points it at each of us in turn. “Holy… how many of you are there?”

“Ten”, I say. “I think we were in virtual reality, or else we travelled in time…”

“I don’t think… I don’t think people wear things like that in heaven. Hell, I don’t even believe in heaven! I think you’re right! Let me have a look at that.” He speaks with a new-found jubilance. He gets up and walks toward me.

He sits down next to me and starts examining my suit.

“Wow, it’s… this must be… how did…”

I scream in pain as he prods at my left knee, and instinctively bend it away from him, which makes it hurt even more.

“I’m sorry, I…”

Some of us cry in sympathy, some in surprise.

“She has a broken kneecap. Do you have any painkillers?” I say. At 18, I’m the second eldest.

“I think so… let me go check.”

“Wait!” I call after him. “Check where? Where are we anyway? Can we go with you?”

“I guess so…” he replies. “You’re… I’m at a retreat, from technology.”

“Already?” I remember suggesting the idea to him; it would be a giant art project, an adventure in the past. I walk with him toward the door.

“I’ve been here for about three and a half years, but there was…”

I feel a gentle tension pulling me back inside, the tingling I used to get at the top of my head when I ran too fast and breathed too little. The cable linking me to the ceiling is fully unwound.

Jack looks up at the cables for the first time, and follows them up with his flashlight. The light is too weak to reach the top. “Wow,” he gasps.

“Please…” calls the ten-year-old. “It hurts!”

“Okay, I’m going to get some stuff. I’ll be right back,” he promises as he leaves.

Here we are again, ten hearts, one name, alone with ourselves. Twenty hazel eyes staring into the darkness. A few more facts and millions more unknowns.

To be continued…

Ten of Hearts: Double You

Posted by Angela Brett in Intriguing Development, Writing Cards and Letters on August 10, 2008

Here we are. Ten hearts, beating silently. Twenty legs, some abruptly collapsed onto the floor. Twenty hands, grasping at lost sensations. Ten heads, linked to flexible cables suspended from above like the strings of ten marionnettes. Twenty hazel eyes, staring into the darkness.

Here we are. Ten hearts, beating silently. Twenty legs, some abruptly collapsed onto the floor. Twenty hands, grasping at lost sensations. Ten heads, linked to flexible cables suspended from above like the strings of ten marionnettes. Twenty hazel eyes, staring into the darkness.

Twenty eyes which were just moments ago watching gummi bears leap around

on a screen, watching the world whiz by from a swing, watching the teacher form the letter W on the blackboard, tracking an approaching ball, streaming tears from the pain of a broken knee, gazing down at polished shoes on the school stage while the students clapped, closing in embarrassment for a first kiss, glazing over in front of an educational video, closing in rapture during an embrace with our soulmate, opening wide in terror.

The cries of the youngest hit our ears before our eyes have adjusted. A sound made by one, forgotten by some, not quite familiar to others. We begin to see each other, ourselves. Some recognise past selves, some gape at the slow recognition of future selves. Some are too young to know that the others have separate thoughts.

We look at each other questioningly, trying to find the right words to say, and wondering whether we need to say them once they’re found.

“Are you me?” I say. I’m twelve, nearly thirteen. I think I wished myself here, to escape the humiliation of standing in front of assembly with my art prize.

All are unsure. Those close to each other in age answer similarly. All who answer answer positively. We are Cat Diesch. We were born on October 10, 2010 to Rose and Macy Diesch. We have no siblings. We enjoy painting, fireworks, and nectarines. We are sitting in a dark room with nine other versions of ourselves, at different ages.

More questions follow. Did we travel through time? How can we travel back? Did we die? Did we all break our kneecaps at ten years old? Only the last gets an answer, so we quiz each other on our lives. We all lived the same one. We each lived it until August 10. Each in a different year, always two years apart. The younger ones are warned not to play rugby, for a broken kneecap is painful.

Very painful. I am ten, and though my world disappeared, my knee still hurts, and my eyes are still streaming with tears. “I want to go back to the hospital,” I plead. Nobody says anything; we know that we have no answer. Less than an hour ago my leg was in a splint, now it is covered with the same smooth, squishy black fabric as the rest of our bodies. As an older me comes to comfort me, I notice the cord linking her to the ceiling unwinds so that she is free to move toward me.

A recently-read novel is still fresh in my mind. “It’s like some kind of virtual reality suit. Do you have that in the future?” I ask my older selves. The one who spoke first says, “Oh yeah, like in… what’s it… World of the World Builders!”

The older ones smile at the spark of a much-enjoyed book lighting up their memory.

“Nothing like this.” I say. I’m eighteen. I tinker with the graphics for the virtual reality software my boyfriend is making for his Master project. He just uses goggles, earpieces, gloves, and some basic neural stimulation.

We ponder in silence for a while, watching the two youngest play together. Our thoughts are like ten flautists playing different tunes, each trying to make sense of the same shrouded score.

“Did I stay with Jason forever?” I ask. I’m fourteen, and I know Jason and I are meant for each other. But after exchanging puzzled looks, my older selves burst out laughing.

“Jason… oh my God, that kid? He was…” They stop when they see the look on my face.

“I remember,” says a sixteen-year-old me. “It feels important now, but believe me, it totally isn’t.”

“And you end up with someone much better,” say the two oldest in unison.

“Who?” I ask. “What’s he like? Is he cute?”

The click of a door interrupts our retrogressive reminiscence.

To be continued…

Nine of Hearts: Broken Symmetry

Posted by Angela Brett in CERN, Old Stuff, Writing Cards and Letters on August 3, 2008

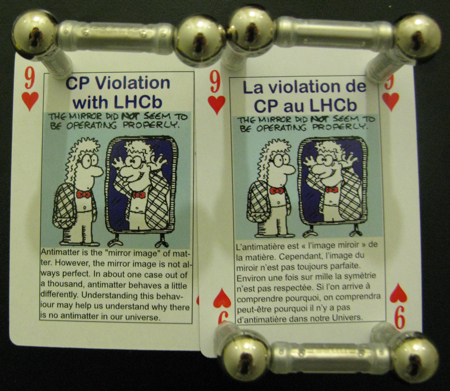

Nines of hearts featuring CP violation at LHCb: The mirror did not seem to be operating properly. Click to see a guardian Angela.

The following is a story I wrote in 1996, unaltered except for one word. This week’s Thing is below it.

Mirror Image

It was not until my twelfth birthday that I realised the face I saw in the mirror was not mine.

I had always assumed it was me – with the long brown hair, hazel eyes, and the line of freckles joining two rosy cheeks. Indeed, that corresponded to the way others hazily described me. The image perfectly mimicked my actions, wore my clothes in the way I imagined they looked on me. I had no reason to doubt that it was my reflection that I could see, as she looked convincingly like photographs of myself.

Ironically, it was my kitten, Angel, who led me to discover what I am sure I was better off not knowing. She was given to me on the birthday which I have mentioned, a cat such a pure white that the name Angel immediately sprang to mind, and stayed there, when I first saw her. The kitten did not seem to have such an angelic temperament, however. As soon as I released her from the box she had been brought to me in, the distressed kitty leapt at my face, giving my cheek a scratch which would have been very painful, had it been caused by a fullgrown cat. Quickly I rushed to the bathroom to inspect the damage in the mirror. I was relieved, though a little puzzled, to see that the scratch had not even marked my face, and went back to my friends in the lounge.

“Ooh, that’s a nasty scratch, Hannah – we should put some Savlon on that,” said my mother.

I thought she was joking, and said, “Oh, of course, it probably needs stitches as well!”

“It’s not that bad, Hannah, it’s just bleeding a little. But we don’t want you getting an infection from the cat.”

“But… there isn’t even a mark! Don’t be silly, Mum.”

“I think you’re the one being silly, Hannah. That scratch sticks out like a sore… like a sore cheek. I’ll get the Savlon.”

By this time even my friends were beginning to look at me strangely, so I didn’t say anything more. Before I went to bed that night I looked in the mirror again, but still no scratch had appeared on the image.

The next day – Sunday – I spent in front of my mirror, examining the image and comparing it to photos. I noticed several subtle differences – her eyes were a slightly different shade, she had a few extra freckles. While I wasn’t looking at the mirror my mind was occupied solely with trying to figure out who she was. Did I have a twin who had died at birth, and now watched me through the mirror? My mother assured me that no, I had never had a twin sister, and wondered why I had asked. I dared not tell her.

So who was it? Soon I became very uncomfortable around mirrors – I did not like the thought of her watching me. By the time I was fifteen my thoughts were permanently filled with dread, the awful feeling of being watched. I started to plan shopping trips so that I could pass as few reflective surfaces as possible – my friends thought I was weird, and soon they were not my friends. I was relieved at this – no longer would I have to think of excuses not to go out.

I covered my bedroom mirror with a blanket – my brothers teased me that I could not stand seeing my own ugly reflection. If only they knew. I was becoming ugly, I knew that – it’s hard to maintain a good appearance without mirrors for makeup, and even harder to look happy when you’re being watched by the devil,

I managed to completely avoid seeing the image for eight months. At times I managed to seem normal. but I was always scheming to avoid her seeing me. My mother sent me to a psychiatrist, but I ran away from there when I saw the reflective silver stars on her walls – meant to be cheerful but instead terrifying. They were only peep-holes for her to watch me through.

Then one day, when I was seventeen, I came home to see my mother had done spring-cleaning. The windows sparkled with a near-transparent image of the spy. Even the netball cups I had won before discovering her were displayed on the mantelpiece, their newly-cleaned silver proudly reflecting what I used to think was me. I ran to the sanctuary of my mirrorless bedroom.

She looked straight at me, taunting me with a replica of my own paranoid face. My mother had cleaned my mirror for me.

I threw a sneaker at the mirror to smash it. She continued to watch me, the face more disfigured by cracks in the glass. I grabbed a sliver of it and thrust it into my chest, preferring death to this life tormented by the devil’s spy. As I slipped into unconsciousness I heard her speak to me.

“You needn’t be afraid… I’m only your guardian angel.”

(now comes the Thing A Week part.)

Mirror Image II

It was not until my twelfth birthday that I realised the face I saw in the mirror was not mine.

I had always assumed it was me – with the long brown hair, hazel eyes, and the line of freckles joining two rosy cheeks. Indeed, that corresponded to the way others hazily described me. The image perfectly mimicked my actions, wore my clothes in the way I imagined they looked on me. I had no reason to doubt that it was my reflection that I could see, as she looked sufficiently like photographs of myself.

It started with a gift. My birthday had been going perfectly, until I opened the last box, a box which been jiggling in anticipation all by itself. Inside was a kitten… perfect, white, and dead.

Our faces went as white as the cat. “Oh Hannah, I’m so sorry!” gasped my mother. “There mustn’t have been enough air in the box… it’s all my fault… I should have…”

I rushed to the bathroom to cover my imminent sobs. But my shock was met by a second shockwave when I saw myself in the mirror. I had a scratch on my cheek, which was bleeding. I went back to the lounge to show my mother.

“Hey, why didn’t you tell me my cheek was scratched? Where’s the Sav?”

My mother’s nervous expression collapsed into a blank stare, too fatigued to complete the transformation to confusion. “Scratched?”

“Yeah, I don’t know how it happened.”

My parents exchanged worried looks, and I wondered if they’d thought I’d hurt myself while doing something naughty.

“I know you’re upset about the cat, but you don’t have to pretend you’re hurt. We promise we’ll get you a new kitten.”

“But I’m not pretending,” I protested, moving my hand to the affected cheek. “I…” I stopped speaking when I felt the smooth, unbroken skin.

“Look, how about we all have birthday cake and try to forget about it for now?” said my dad.

So I pretended to forget. It was easy to let my family think I was upset about the cat, and not the phantom scratch. Before I went to bed that night I looked in the mirror again. The scratch was still there, but already starting to heal over.

I spent all the next day in front of my mirror, examining the image and comparing it to photos. I noticed several subtle differences – her eyes were a slightly different shade, she had fewer freckles. And she had that scratch. I wondered what had happened to her. I hoped that it did not hurt her too much. I hoped that she wasn’t my own future.

So where did she come from? I asked my mother if I’d ever had a twin sister. She looked at me the same way she had when I’d asked about the scratch, and said no. I knew better than to continue and risk being sent to a nuthouse. I told her not to worry about getting a new cat.

After that, my reflection always looked a little scared, and maybe I did as well. It sure felt weird to look in a mirror and know that there was somebody else looking into my world. I wished I could ask her who she was, what was troubling her.

A few times I thought I saw a white cat in the background. Had my kitty escaped into her dimension, or was I subconsciously so upset about her that I saw her everywhere?

As time went on, I began feeling increasingly uneasy, even when I wasn’t looking in a mirror. I kept having the feeling that something wasn’t quite right, something in my peripheral vision that escaped my attention. It was my little brother Bob who first realised what it was, as we walked past some shop windows one Saturday.

“Hey, Han, you’re a vampire!”

“And you’re a tasty little troll!” I retorted, leaping toward him in mock menace.

He bolted with a shriek of true terror, bawling and screaming until he was out of sight.

“Geez, I was only joking!” I said to my parents. “You’d think at ten, he wouldn’t be scared so easily!”

It took us fifteen minutes to find Bob again, and another half an hour to coax him out of his hiding place. When we got home, he raced to his room.

“Bobby,” I called through the door. “You know I was only joking, why’d you run away like that?”

“Go away!”

After much pleading, he eventually let me in. He was wearing two sets of rosary beads and clinging to a Bible. I couldn’t help laughing, and he almost joined me with a slight smile. I sat as close to him as he would allow. The fear returned to his face, and he pointed to his mirror.

When I saw his pale face in the mirror, I felt my own face go white. I felt it, but did not see it; in the reflection, Bob was scared and alone. I had no reflection.

“I swear I’m not a vampire,” I said. I explained what had happened. I’m sure I was even more relieved than he was that the truth was finally out. He seemed especially happy to hear that my doppelgänger had the cat.

“Can I tell you a secret?” asked Bob.

“Sure… if you can trust your secrets to a vampire,” I grinned reassuringly.

“When I was a little kid, I used to think my reflection was my guardian angel. I tried moving really fast to see if he would keep up with me. I swear sometimes he didn’t. And we played rock paper scissors against each other. But when I grew up, I thought I had just made it up when Dad read to me about Peter Pan’s shadow.”

I stared at him, wide-eyed.

“Maybe you’re right. Maybe our reflections are all guardian angels. But what happened to mine?”

It was a scary black hole of a question, which got deeper as reflections kept disappearing. Soon my bedroom mirror showed only darkness. I was afraid to touch it, lest I be drawn into a dark mirror-world.

I longed to see her again, to reassure both of us that we were not alone. I grew much closer to my brother, who would tell me whether I’d combed my hair straight, and let me sit with him and his own reflection when I missed my own. The secret stayed between us. I stayed away from mirrors in public, and found that most people did not notice the missing reflections in other shiny surfaces.

One day, when I was seventeen, I came home to see my mother had done some spring-cleaning. And it was more than just a clean. The windows, my trophies, everything was so clean that I could see my reflection in it. I rushed to my room to at last get a good view of my angel, afraid that she would soon disappear again.

There she was, looking so scared that I tried to reach out and comfort her. She responded by throwing a sneaker at me.

The mirror remained intact, but the image broke into shards, reflecting pieces of her strangely unfamiliar bedroom. I tried to make sense of the images speeding across one shard, until I saw the end of it reflecting what was unmistakably blood. I watched as the blood took over the rest of the shard, and sprayed onto the others. I watched her beating heart approaching me from the mirror. Too late, I realised who needed to protect whom. Too late, I told her what we both needed to hear.

“You needn’t be afraid… I’m only your guardian angel.”

And for one last time, the mirror was accurate. As her heart stopped beating, my heart broke.

Five of Hearts: Amiaivel

Posted by Angela Brett in Birds of Canada, Writing Cards and Letters on July 6, 2008

Once upon a time a queen was blessed with twin sons, which she named Nosch and Amiaivel.

Nosch fought his way out of the womb a few minutes ahead of Amiaivel, and thus thought himself the eldest. He knew that this meant he would become king, so he always demanded too many entitlements, and looked upon his twin as a slave. Amiaivel had a kind soul, and could not allow himself to deny his own twin’s demands. But the wise queen saw this, and as she began to get old, she announced to the people that Amiaivel would become king when she died.

Nosch was incensed that the second twin would steal his position, so he called upon a witch to cast a spell upon Amiaivel. The spell made Amiaivel, his fiancée Bella, and his maids into toads, and locked them in a dungeon beneath the vegetable patch.

Much time passed, and Amiaivel contented himself with talking and singing to his toad maidens. One day, a pixie floated in on a golden plume.

“Soon, the son of King Nosch will come to see you,” said the pixie. “He will demand the most beautiful shawl in existence. If you give him the one that the elves gave Bella as an engagement gift, then you will soon become human again, and be let back into the palace.”

As soon as the pixie had left, a young man descended into the toads’ dungeon.

“Excuse me, good toad,” he said. “I am Tais, the son of King Nosch. I seek the most beautiful shawl in existence. Can you help me?”

Though it pained him to give away such a valued keepsake, Amiaivel asked one of his maids to give it to him, and said, “This is the most beautiful shawl in existence, and one of my most valued posessions. Take it. I wish you good luck.”

Tais thanked him and left. By and by, the pixie came back.

“I must again ask a good deed,” she said. “The king’s son will come back seeking the most beautiful jewel in existence. If you give him Bella’s engagement band, then you will soon become human again, and be let back into the palace.”

In no time, the young man came back. “I am most unhappy to have to annoy you again, but I must find the most beautiful jewel in existence. Can you help me?”

Amiaivel hesitated to give up the symbol of his and Bella’s love, but knowing that the love itself would not lessen, he gave Tais the engagement band. “On this band is mounted the most beautiful jewel in existence, and one of my most valued posessions. Take it. I wish you good luck.”

Amiaivel sat glumly in his dull dungeon, awaiting the pixie. She fell into the jail with a potato plucked out of the soil above. “I can not yet fulfil my pledge, I must yet again ask you to give up something you love,” she said.

“I have nothing left to give. Make me human, I beg you!”

The pixie paid no attention to his plea. “This is a magic potato. If you put a lady toad in it, she will become human,” she announced. “When the king’s son comes to see you next time, he will need the most beautiful maiden in existence. Let Bella climb into the potato and leave with him, and you will soon become human again, and be let back into the palace.”

In a little while, Tais came to visit. “Again, I am most apologetic to ask an act of kindness. But I must fetch the king the most beautiful maiden in existence. Can you help me?”

Amiaivel had lost too much to his hateful twin, and could not give his fiancée to him as well. He gave the potato to Tais and showed him Puzchunza, his most beautiful housemaid. “Hollow out the potato and put this toad in it. The toad will become the most beautiful maiden in existence, and the one that I love the most. Take the maiden to the king. I wish you good luck.”

So the king’s son hollowed out the potato, and put the toad inside. As soon as he had done so, the toad became a maid, and the potato became a coach. Tais kissed the maid, and they left.

Again, Amiaivel sat and awaited the pixie. But she did not come. Many weeks he waited, until finally somebody came. This time it was Tais.

“Thou hast shown me immense kindness,” he said. “Because of thee, I have become king. In thanks, I would like to help thee,” he continued. “A pixie told me that thou beest my uncle, locked in a toad’s body by the late King Nosch. So I have found a good witch, who gave me this potion to heal you. Alas, she could not make enough to save thy housemaids.”

Amiaivel swallowed the potion, and instantly became human, still as young as he had been when he was enchanted. He went up to the palace, and was taken to Puzchunza, and given Bella’s engagement band. “Since this is the lady thou lovest the most, she will be thy wife.”

At once Amiaivel began to sob. “I lied. She is but my maid. My fiancée is still a toad! Oh, if only I had not been so selfish!” With that, Amiaivel dashed back into his cave, and found the middle pieces of potato which had been left behind. He massaged Bella with them, and soon she became human. But alas, not enough potato was left. She still had one leg like that of a toad, and skin pocked with boils. But she was still his beloved.

Amiaivel helped his fiancée to the palace, and soon they wed. Tais had fallen in love with Puzchunza, and was glad that she was not, in fact, Amiaivel’s fiancée. Those two also wed, and the two couples united to lead the kingdom with wisdom exceeding that of any single king.

Ten of Spades: The Fungus Who Ruled the World

Posted by Angela Brett in Pilze, Writing Cards and Letters on May 11, 2008

I am the master of my environment. The king of the fifth kingdom. My sweet chestnut tree delivers all the nutrients I need. I have no need for even a brain to live in this paradise on a lesser creature. Nothing needs to change; even in the far future, if my tree dies, my descendents can continue to feed on it. This forest belongs to us.

With food security like this, it does not matter that I am incapable of surviving without my host. I have everything I need. I do not need to move, I do not wish to move, and, because a perfect design has no superfluous features, I have no ability to move.

And yet, I am moving. I am being pulled from my life source. Pulled by something even more powerful than myself.

I can no longer pretend that I am the master of my environment, above the rest of the animal kingdom. I can not go on as a parasite on less fortunate creatures, raising and killing them just because I have a big enough brain to know how. Something has to change. There are simply not enough resources to continue transforming large amounts of food into small amounts of meat. I want something to be left for my descendents. This forest belongs to nobody, and we have no right to destroy it for pasture.

I’m perfectly capable of surviving without meat. I can get all the nutrition I need from fruits, vegetables, chestnuts from the forest, mushrooms… ah, now here’s a beef steak I can eat without troubling my conscience.

I pull the beefsteak fungus from the treetrunk and take it home for dinner. I need not exercise my power over nature tonight.

Six of Spades: Three perspectives on CERN Open Days

Posted by Angela Brett in CERN, Writing Cards and Letters on April 13, 2008

Strong: Did you miss the CERN Open Day? I did, in 2004. It wasn’t my last chance.

Strong: Did you miss the CERN Open Day? I did, in 2004. It wasn’t my last chance.

I planned my visit to CERN far in advance, and found out on my arrival that an open day was planned for a few weeks after my departure.

Thanks to an Englishman arranging a lift, I did manage to get to CERN’s 50th birthday party in Crozet. The speeches were enlightening… I had never realised that humans could make such bizarre sounds. What they were saying in French, I could only guess. My English companion had learnt enough French at school to understand some of it. From him I learnt one of my first words of French: Cernois, a person who works at CERN.

I wrote in my travel log:

After I’d looked at everything, I bought too much stuff at the souvenir shop, just like I did at the Apple Campus. The reason is the same — ‘when am I ever going to be here again?’ and so is the answer to that rhetorical question… when I work there.

A month before writing that, I had found out that my application for a CERN junior fellowship had been rejected. While still in Geneva, I found out that I had not been accepted into CERN’s Marie Curie fellowship programme either. So when I got home, I applied again.

My Marie Curie fellowship began in April 2005 and ended two years later. Before the end of the fellowship, I had been offered a position at ETH Zurich, based at CERN, so I continued going to work as usual, inasmuch as working at the world’s largest scientific facility can be considered usual.

That September, I got wind that CERN would be having open days the following April. I sent the news to everybody I knew, hoping that with enough notice, nobody with the slightest chance of making it to Geneva would miss out as narrowly as I had. I realised that as a Cernoise, I had the once-in-a-lifetime chance of not only going to a CERN open day, but being part of it. So I signed up as a volunteer for the Cernois-only open day on the Saturday.

Weak: I arrived at CERN at 8a.m, and was given a lift to the CMS pit in Cessy by a colleague and fellow volunteer. We all had our official T-shirts, windbreakers, and polar fleeces, several sizes too large. Guides had their hard hats, the people at the info point had their souvenirs to sell, physicists had brains brimming with answers, and I… I had tables, paper, coloured pencils, and pictures of CMS for colouring in. Kids’ corner.

After lunch I found myself alone at the art table, with two children approaching. Their mother asked in French if this was where they would be minded while she went underground, and would I like to take down her phone number? Would I? I had no idea. I looked around, only to have some guides confirm that it was indeed me in charge of the kids’ corner.

I mutely took the number, and finally the mother asked me in English whether I spoke French. Oui, oui, bien sûr… I like to pretend that I do. She explained to her kids that I didn’t. By this time the kids had the idea that I was a little odd, and sat there glumly staring. I asked in French if they wanted to draw something. They didn’t. The older one started halfheartedly colouring in. I tried to bribe them with promises of prizes for good drawing. They did not respond. Not sure of what else to do, I sat and dutifully watched them, feeling like some kind of psychopath. I started drawing, in an attempt to look less like one. Anyone who had seen my drawings would not have been convinced.

To my relief, a friend appeared with his young nephews, and I talked to him for a while, occasionally checking that my charges hadn’t exploded.

When the mother finally came to rescue her children from their ill-adapted babysitter, the younger one, who had barely touched his pencils, didn’t want to go. Perhaps, in the end, I am quite interesting to glumly stare at. I probably would have held the Cernois in awe too, if I’d been a member of the public at the 2004 open day.

Electric: Sunday was the open day for the general public, and the day when I, too, would be in the general public rather than a volunteer.

The bus to CERN was almost full at its first stop. It was great to see that I wasn’t the only one excited about the open day. At CERN, there were already crowds surrounding the Globe of Science and Innovation, near the entry to visit the ATLAS experiment. I’d already seen ATLAS, thanks to a friend who was trained as an ATLAS guide, so I headed into the rest of the site to see what else there was to see.

The whole place was eerily quiet. I saw a few signs, but no crowds to show me what might be interesting. I went to the café in bulding 40, knowing that there should be some events there, or at least some coffee. There were more volunteers than visitors, and no food yet. Still five minutes until the official start of the open day.

The restaurant was not crowded. I bumped into the friend from the day before, with his nephews and the rest of the family. Was it another day for the Cernois, after all? I checked the volunteers’ interface on the web. There was a few hours wait to visit ATLAS. The amateur radio club was still waiting for visitors. Shuttles supposed to take people from the Meyrin site to visit the ALICE experiment had still not arrived. At 9:30, I heard that some friends of mine who had come from Lausanne early that morning had already been underground to see CMS. What was going on?

What was going on was that 20 000 people were going underground to see the LHC and the detectors. 20 000 out of a previously stated maximum limit of 15 000.

The first visitors arrived at CMS at 7a.m. With queues filling the detector assembly hall and stretching hundreds of metres down the street, there was little choice but to start the underground visits half an hour early, at 8:30. The elevators ran at full capacity and full speed. At LHCb, tour sizes were kept smaller in order to allow more foreign language tours, but they still had a huge number of visitors. By 11a.m. the waiting time to see ATLAS was close to four hours.

Meanwhile, the rest of the 53 000 visitors were dispersed around the various sites, watching machines making machines, Nobel prizewinners making revelations, superconducting magnets making people and things fly, superfluids making their way up the walls of their containers, and actors making out they’d lost some protons.

By the end of the day, the forecast cold and rain had finally arrived. My friends drove me the short distance to the bus stop, where a busload of people were already waiting. One had come from London. One from Paris. One was an art student from Lausanne, who was more interested in the logo and other designs used for the event. One was a guide for CMS, who had volunteered to guide people in English and Portuguese, but ended up speaking French all day and getting a sore throat from it. When the bus arrived, the crowd surrounded it like a plague of zombies… but so much more alive.

Four of Spades: Lake of many Rivers

Posted by Angela Brett in Discover Ontario, Writing Cards and Letters on March 30, 2008

Two of Spades: Sleeping Giant

Posted by Angela Brett in Discover Ontario, Writing Cards and Letters on March 16, 2008

Gareth lay still for a minute listening to the music before reluctantly opening his eyes. He scrunched them closed again at the sight of his bedside lamp, still glaring since his insomnia of a few hours earlier. Gradually he coaxed his eyes to open again and focus on his laptop screen to check his mail. Nothing worthwhile. His eyes, at last awake enough to exercise their own free will, moved toward the small capsule resting on his bedside table. His brain, not awake enough to remember how much he wanted it, dismissed the idea of swallowing the pill. His body took him to the shower and turned on the water.

While the warm water meandered over his body, his cold mind meandered around the thoughts he didn’t want to think. Suddenly he was struck by a memory from his dream. He had lost her again.

In the dream she was blonde, and he couldn’t recall her face, but he knew that it was her, the feelings were the same. They were on a cliff overlooking their village on the black plains. He knew that it was forbidden, but there was no better place to propose to his sweetheart. He remembered how contented he felt, holding her hand and gazing down at all Creation. Until a freak wind blew her away, and left her motionless on the plains below. He remembered jumping down from the high cliff and landing unscathed, thinking nothing of the feat, and running to her. His dear Bea lay there, brunette again, her face returned, but bleeding and empty of expression.

The dream stayed with him all day. From time to time he would catch himself thinking that he really did live in that village on the black plains. It seemed like an age he had lived in that place. It seemed like only last night that he had lost her. Only last night he had gazed into those lifeless eyes, wishing he could forgive himself.

The day came and went without his paying much attention to it, and all too soon he was back in his bed, staring at the capsule, wondering whether a temporary sleep would claim him before he claimed a permanent one.

He couldn’t go back to the village after that. He couldn’t stand the thought of a hundred villagers obliged to act sympathetic while attempting to hide their ‘I told you so’s behind transparent corneas. He couldn’t stand the thought of living at all without her. He couldn’t stand the thought of the villagers aiming their phoney sympathy at his dead body. He stole a container of poison from the apothecary and stole back toward the cliff.

Sheets of bristled vegetation made the climb easy. Soon he was gazing back on the village again. This had been his favourite place in the world. The perfect place to die, were it not for the thought of villagers finding him. He turned toward the forbidden plateau. Beds of ground cover spread so far in front of him they made him tired. He began walking.

For hours he walked, as if in a dream. Distant hills appeared, and steadily grew in his field of view until it seemed he could easily reach them. How nice it would be to end his life high up, at a lookout spot like his own. He stopped to rest, and imagined he heard music.

Morning again. Gareth marvelled at the way even his favourite songs could become hated when given the task of waking him. Another day of emptiness, of working, of trying not to think. At midnight he fell reluctantly into his bed, for the nightly face-off with the pill. It had wandered from his night-table onto his mattress, as if trying to tempt him. Did it want him to swallow it? Did he want to swallow it? God knew he didn’t want to continue life like this. He held it a long time in his fingers, staring at it, mentally conversing with it, not quite gathering the courage to crush it between his teeth. Near morning, it fell from his grip as he lapsed into a troubled sleep.

When Gareth came out of his reverie, it seemed the hills were further away than before. Perhaps their nearness had just been wishful thinking. He continued on his way. As he approached the hills, he perceived a higher cliff atop them, nearly devoid of plants. The view from the hill was unimpressive, the monotonous plateau blocking the view of the plains. He started up the cliff face, grabbing the occasional stubbly brown stalk for support. Several times he fell.

Suddenly, he felt a great wind pressing him into the cliff. He turned his head sideways, his cheek pressed against the rock face, to see that the wind was followed by what resembled a giant stone hand.

He scrambled sideways to escape being crushed. The hand missed him by a whisker, but the force of it hitting the cliff caused such a quake that he fell back to the hill.

Dazed, Gareth wondered whether this was why the villagers told such tales of the plateau. Perhaps there was something to their superstitions. But he had never believed in such rubbish. The world was the way it was because of natural laws; there were no ghosts, no giants, no winds of God to punish the disobedient. It was all coincidence, it could all be explained.

Armed with this revived stubbornness and curiosity, Gareth resumed his climb. As he neared the top, he gripped one last ridge and pulled himself over it.

There was no solid ground beneath his torso. He found himself hanging headfirst from the lip of a chasm. Steam rose over his face and obscured his vision. His grip slipped on the slimy stone. He flailed blindly with his other arm, which found some thick vines further along the edge of the chasm. With all his strength he pulled himself across, and found a safe place to sit near the lip of the volcano.

Shaken, he looked back towards where he’d come. The hills, the plateau, the black plains, stretched out in front of him. And beyond… he could see that even the plain was a high plateau. He could just make out some strange figures strewn over the ground below it. He wondered if there were villages down there as well. What must they be like?

At last he remembered what he had come for. He had seen everything on Earth, but the most important piece was missing. What good was all this without her? He opened the flask of poison and brought it to his lips.

As he tipped the flask, he recalled the terror he had felt when falling into the volcano. How desperate he had been to escape. Why hadn’t he let himself fall? His survival instinct did not fail him. Somehow, deep down, he wanted to live. He wanted to explore all the lands he could see. He would never find Bea again, but perhaps he would find happiness.

Fearful of changing his mind, Gareth tipped the contents of the flask into the mouth of the volcano. For a few seconds, he was again at peace with the world, the way he had felt on his old lookout point on the cliff.

Suddenly the ground hiccoughed violently. He managed to remain in place only by gripping the vines. He had barely begun to feel safe again when the world seemed to melt, and the sky was lit with visions of Heaven, of Hell, of his parents, of Bea… nothing made sense. He became aware that as the visions faded, the sky faded as well, until all was black except for a shrinking circle of light around the Sun. An old science lesson came back to him… didn’t they say that if there were no atmosphere to diffuse the Sun’s rays, we would only see the sun surrounded by blackness, like a star?

At this thought, the air seemed to thin, and he could no longer breathe. Unconsciousness overtook him just as his dreamworld disappeared.